Imagine, a 10-year-old girl studying in a government primary school in the rural hinterlands of India. Every day she walks to school with her younger sister. The Right To Education Act has ensured that she has access to a school close to her village hamlet, unlike her parents’ generation. The State government has poured in resources to ensure digital tablets and internet connectivity in the school. For her, this the only place she can have access to learning, technology, an assured meal through the Mid-Day Meal Scheme, but there are still gaps in the school infrastructure. There are hardly any inspections by government officers, and since an operational school in the area is a huge advance on the opportunities available some years ago, no one seems to mind the odd laxity in standards. One day her sister falls ill, most probably because she used the unhygienic toilet at school, which is not cleaned regularly. She has to stay back to take care of her sister at home because both her parents are wage labourers, who have to travel every day to make a living, sometime working as MNREGA labourers, travelling to the nearest town or tilling fields of other during sowing and harvest season. Both sisters miss several days of school and fall behind the syllabus. Eventually, they drop out and never return to school.

This hypothetical is all too familiar in several parts of the country and is just one instance of some of the issues in public service delivery. Service delivery through government institutions in India faces challenges of maintaining the quality of the service on one hand and ensuring remedial action on the other. Not only is a uniform standard required to evaluate hygiene conditions in schools, but this standard also needs to be deployed in a manner which ensures regular inspection and monitoring. The problem is as much an issue of scale as it is of streamlining the inspection hierarchy. With overstretched manpower at the bottom of the administrative pyramid and dispersed settlements in rural areas, there is a risk that the quality of services will fall far below the level envisioned.

The use of an AI engine developed by Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) for the Andhra Pradesh State Government School Education Department to monitor sanitation of government school toilets offers a way forward. Use of this technology has resulted in saving substantial manual effort in tracking. It has also contributed to a 12% increase in enrolments since its rollout and 60% year-on-year reduction in girl child dropouts. The Government of Andhra Pradesh wanted to maximise attendance of its students, especially the girl children, in all schools by taking up various measures such as upgrading the school infrastructure including toilet facilities through the Mana Badi – Nadu Nedu Programme. The scheme covers 45,000 schools with approximately 50 lakh enrolled students.

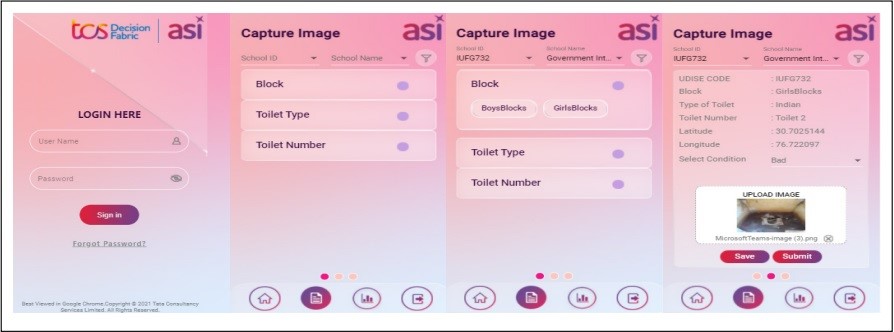

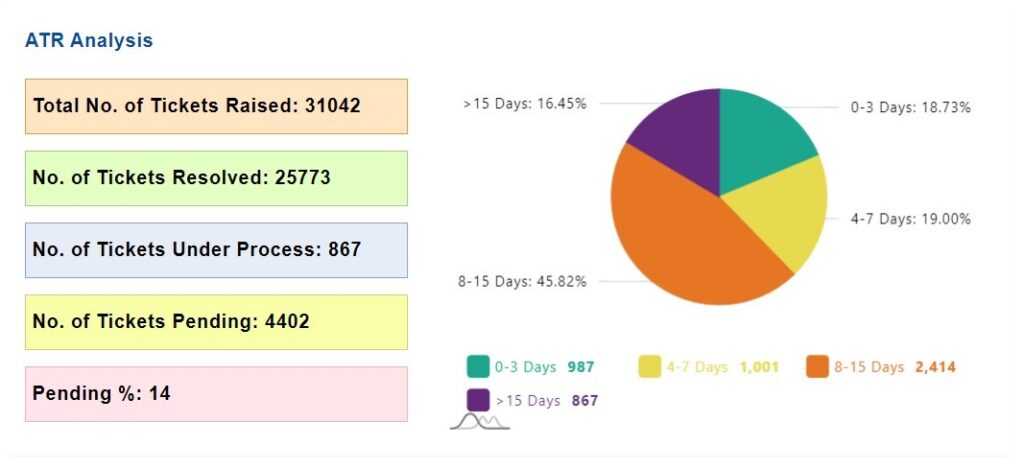

Lack of clean toilets in school has a negative impact on the health of children. It also affects attendance, especially of girls. Apart from behaviour change interventions, regular inspection and corrective action are required for ensuring hygienic conditions in these toilets. Without technology, this would mean daily physical inspections of 45,000 government schools in the state as well as reporting to authorities and monitoring remedial action. This was also impossible to ensure earlier. TCS offers inspection as a service to its business clients using AI and the Andhra Pradesh government recognised this as an opportunity. TCS has developed a tailored Intelligent Sanitation Assurance solution, with a custom-built mobile app, to ensure continuous and regular cleanliness monitoring automation. The App is used by school staff to take photos of the school toilets, urinals, wash basins etc. The photos are geotagged and time-stamped and the AI engine is then used to process these images. The engine classifies the toilets as “good” or “bad”, and a ticket is automatically raised for all “bad” toilets, alerting authorities that remedial action is needed.

Every school in Andhra Pradesh receives a Toilet Maintenance Fund (TMF) from the state government. The data from the TCS AI engine is fed automatically into the open access dashboard of TMF and the fund is utilised to take corrective steps in case the engine identifies a toilet as “bad”. This helps drive transparency by publicly tracking the impact of the ₹440 Cr Toilet Maintenance Fund, used for the cleaning supplies, sanitation workers and other necessary actions identified from these reports.

The app automates the entire process of inspection, thereby eliminating the need to deploy another layer of government employees in the fields, accompanied by supervisory layers to ensure there is no gap in the process. This saves manpower and subjectivity in the inspection process. The application is processing about five lakh images daily in less than two hours. School staff take photographs using the app and the quality of sanitation is evaluated without going through multiple levels of hierarchy. Inspector based monitoring systems are also vulnerable to corruption and subversion, and a technology-based model removes these weaknesses. The app cuts short the time taken in corrective action through its automatic ticketing system. As soon as a ticket is raised on the dashboard, all stakeholders are aware of the need for action. This presents a unique model of citizen centric governance, where the open access dashboard can become a basis for local communities to track the condition of toilets and other facilities in school, and press authorities for action. Further, the dashboard does offer what it claims – a real time system for continuous monitoring deployed efficiently throughout the state. This app offers vast advantages over a labour-intensive spot inspection approach, and the Andhra government deserves commendation for making this data public on a real-time basis – this model needs to be emulated across the country.

A natural extension of the TCS solution is its use to monitor sanitation in general. India is trying to move away from use of landfills and dumpsites for waste disposals. Deployment of AI in Urban Local Body Areas to monitor and inspect sites traditionally used to dump waste, will ensure that stakeholders find alternative means to dispose of waste. The sanitation and hygiene of all public areas can be continuously monitored through this approach. The app may be used by ULB employees such as Safai Karmis and volunteers to send regular updates about an area. Another obvious sphere, also one associated with government schools, is the Mid-Day Meal Scheme. The quality of meals varies widely across schools and states, and often they are cooked at homes of teachers or others, due to inadequate or unclean facilities in the school. An AI engine deployed across India will allow monitoring of the nutritional value and quality of MDM with minimal effort. This will do away with instances of ad hoc action against school authorities based on videos or news report. The kind of continuous monitoring offered by TCS, will ensure that MDM quality remains high.

The AI solution also has applicability in other developing countries faced with challenges of providing public goods to large populations in the face of fiscal constraints. The idea of inspection as a service can be deployed in nations of the Global South, which are currently pursuing an expensive labour-intensive approach to inspection by deploying staff across the country. TCS’ AI solutions, tailored for specific sectors, can bring in transparency, save costs and ensure real time monitoring of public goods and services in all these areas. It will relieve the burden of the short-staffed government authorities, while providing a more effective means to inspect the quality of these goods and services. There may be several other use cases for this solution ranging from construction, MGNREGA works, operation of Primary Health Care Centres etc. However, there are certain considerations in deploying this model across diverse sectors.

TCS has designed a solution based on emergent technology that can streamline the discharge of welfare functions of the government. The success of this project in Andhra Pradesh offers a means through which smart governance can be institutionalised by eliminating lags in inspections and government action. While tailored solutions for every sphere will have to be built, technology is an effective means to tackle governance challenges. Faced with fiscal constraints, growing developmental challenges due to COVID-19 and limited manpower, state institutions must evaluate how to harness this potential. Automated, transparent, and real time inspection will ensure that public services reach individuals, whose life chances are fundamentally altered by a single day the system doesn’t function. Imagine, what a difference that will make!

Shantanu Pratap Singh is a civil servant and wildlife enthusiast