Very little is known about Jalal al-din Kashani (1863-1926) before his Calcutta days. He came from a modest background in the central Iranian city of Kashan. He was probably trained as an akhund (one who reads the Quran), and even though he hardly ever made his living as an ‘alim, he never gave up the long flowing robe and the white turban that identifies one. It would seem that like so many other ‘ulema of the lower echelons, he engaged in trade to make ends meet. Opportunities were opening up for long-distance commerce in the Persian Gulf region on account of steady British penetration in the second half of the nineteenth century. Jalal landed up in Calcutta sometime around 1888 after trying his hand in Turkey and Egypt, passing through Bombay, Madras, Penang, Java, Singapore and possibly Rangoon, dealing in carpets.

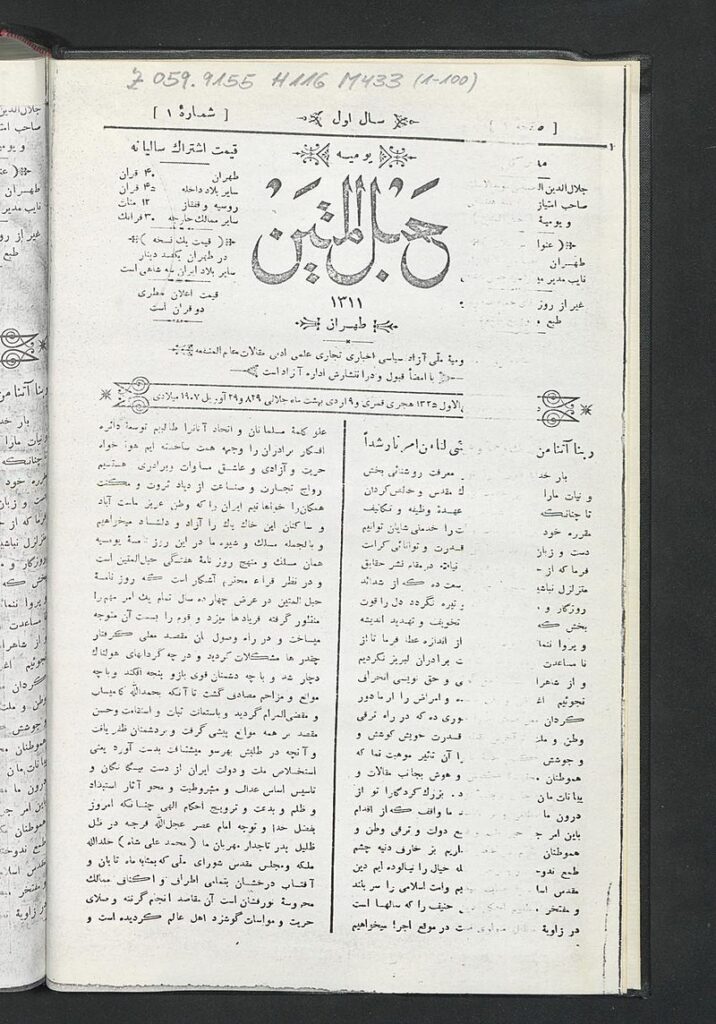

He launched Habl al-Matin in December 1893 as a weekly Persian periodical, giving news about the Kingdom of Persia and subsequently of those countries which had Persian communities. It swiftly acquired a regular readership in Calcutta, Singapore, Rangoon and of course inside the Kingdom of Persia – furnishing as it did news from sarzameen-e Iran to those outside, and from outside Iran to those in the kingdom.

Jalal al-din began the venture largely by himself, with crucial support from his brother Sayyed Hassan Kashani. Subsequently they had professional help, including a managing editor from the sixth year, Muhammad Jawad Shirazi and Ali Asghar Rahimzada Safavi in the later years (hailing from other Iranian families settled in Calcutta). Nevertheless, Jalal al-din remained the driving force behind the publication – to the point that despite having gone blind during the last decade of his life, he would still insist on writing all or most of the editorials himself.

Jalal al-din was able to bring out his journal with fairly detailed coverage of the kingdom of Persia and also about the lives of the widely dispersed Persian community on account of the improved connectivity provided by the colonial apparatus of the Raj. Though the journal may not have had correspondents on its payroll inside Iran, it may have brought in freelance correspondents. Their contribution, when it was not sent through telegraph (because of their size, or cost of sending, or both), would be carried by a network of merchants travelling in fast steamships between Persia and India.

Both among the expatriate Persian communities at different cities as well as back home in the kingdom, the journal mostly travelled through the channels of the mercantile network. Very often, on account of its critical tone towards the Qajar monarchy, influential traders subscribed for a large number of copies, which would then be distributed free to mobilise opinion against the royal court. When circulation of Habl al-Matin was intermittently banned in the Kingdom of Persia, the journal was smuggled in by merchants along with their legitimate merchandise.

Habl al-Matin does not seem to have made much money, despite its wide circulation. Though it carried some advertisements but it chiefly depended on subscription revenue. Jalal al-din’s wife is known frequently to have complained that the old man sunk his family’s entire wealth from trade into the venture. Unusually for a Persian publication in India those days, for the better part of its existence the newspaper was being printed in Jalal al-din’s own press. The press was known for some of its other printing ventures, including Urdu and English newspapers, which indicates that at some stage the concern was making enough money to embark on such ventures.

Impact of Habl al-Matin in Persia

During the first five years, including the years of the fateful Tobacco Protests, Habl al-Matin was not very critical of the Shah. From 1898 onwards, the tone and content of Habl al-Matin became increasingly critical of the Qajar monarchy, making a strong pitch for reform and accountable government. By 1906, Habl al-Matin established itself as one of the most widely circulated publications dealing with the Persianate world, and increasingly preoccupied with the Kingdom of Persia itself.

This shift in the journal’s approach was perhaps prompted by the policies of the new ruler, Muzaffar al-din Shah (1896-1906), which were immensely unpopular among the very social groups that provided Habl al-Matin its readership. In the wake of increased tariffs on native merchants, withdrawal of tax farms from their holders, and prospective increase in land taxes, decrease in court pensions (especially to the ‘ulema) and tightening state control over waqf holdings, a broad swathe of the traditional components of the Iranian society were adversely affected. The Shah was also opening up Iran to European powers in an unprecedented manner. In this backdrop, Habl al-Matin strongly argued for limiting the authority of the monarchy by the institution of a constitution, fashioning in the process what could be loosely labelled as Muslim Iranian public opinion.

The Shah responded by repeatedly banning Habl al-Matin, which, made it even more critical of the monarchy, and hence more popular. During this period, papers like Habl al-Matin helped to shape a new Iranian identity based on territorial jurisdiction and called for a greater role of the people in the political affairs of the country. In public perception, the erosion of legitimacy of the Qajar dynasty owed in a big measure to the criticism of publications like the Habl al-Matin. The contribution of Habl al-Matin in shaping this discourse was later acknowledged by the ‘ulema subsequently lauding the publication as roznameh-ye Muqaddas (the Sacred Journal).

The Afterlife of Habl al-Matin

Muzaffar Shah died in 1906, granting his people the constitutional government they sought so badly. A constituent and legislative assembly (Majlis) was formed to which the government led by the Prime Minister was made accountable. The next few years saw a bitter fight among the various factions but ended with the final triumph of the constitutionalists in 1909. In course of this entire period, Habl al-Matin emerged as one of the greatest voices for mashrutiyat (constitutionalism). Ironically, this was also the period that the publicationbegan to lose its significance, as the new government’s commitment to freedom of speech led to a proliferation of newspapers.

Perhaps to take advantage of the situation, Jalal al-din’s most trusted associate, his brother Hassan Kashani decided to move to Tehran and start a daily and a more radical version of the Habl al-Matin there. The daily was published six days of the week, with the seventh day being left for the weekly. The dailywas published initially from Tehran and then for a while from Rasht (till July 1909).

Conclusion

Jalal al-din Kashani went on publishing Habl al-Matin till his death in 1926, steadfast in his support for further reform and territorial integrity of the kingdom of Persia. After his demise, his daughter continued the venture for four more years before it was finally shut down. The Calcutta-based publication attained the height of its influence before the Mashruteh revolution, at an age when there were very few truly independent voices of criticism in the kingdom of Persia. It was a pivotal factor in the shaping of the political discourse of the Qajar era from the 1890s. By undermining the political legitimacy of the Qajars, it paved the way for the Mashruteh revolution of 1906. Thereafter, even though Habl al-Matin remained popular, and to an extent revered, it lost its previous influence as the world of print journalism opened up in the Kingdom.

During and after the Mashruteh revolution, the idea was broached before Jalal al-din that he should return to Persia, which he politely turned down. While Jalal returned at least once to receive official recognition for his contribution to the revolution (and maybe on other occasions as well), he opted to settle down in Calcutta. Coming from a traditional clerical family of small town Iran, the relative prosperity and the business and social connections, he and his family enjoyed in Calcutta, probably persuaded him to stay back. His five daughters went on to be either persons of accomplishment in their own rights, or ended up married to distinguished people, and settled down in different parts of the subcontinent.

Did Jalal al-din Kashani, over time, become an Indian friend with an Iranian self, or was he an Iranian friend with an Indian self? In an age when identities tended to be as fluid as frontiers for people living in, and moving between, South Asia and the Middle East the question would probably have been somewhat anachronistic. It is perhaps more correct to talk of the ‘firm cord’ that bound people living across the regions, and the manner in which the ideas flowed from one region to influence the lives of others elsewhere.

KIngshuk Chatterjee is a Professor in the Department of History, Calcutta University and Director of Centre for Global Studies, Kolkata