While talking about India-Indonesia civilisational ties spreading over two millennia, Hindu and Buddhist influences are commonly mentioned but Indian merchants and Sufi saints were, to a large extent, responsible for introducing Islam in Indonesia. Today Indonesia is the largest Muslim nation in the world, but Islam took six hundred years to grow roots in Southeast Asia. Though Muslim traders were a familiar sight for long, the first Muslim state came up at Samudra Pasai at the eastern- most corner of Indonesia,–at Banda Aceh, around 1300 CE. It was here at the eastern most corner of Indonesia that the foreign merchants were most closely involved in commercial operations as well as administration. Ibn Battuta, the inveterate Maghrebi traveller (1304-1369) reached Aceh in 1345 and noted that Samudra Pasai was the eastern most Islamic state in the world then.

In fact, the rise of Islam created an unprecedented trading network in the Indian Ocean. Islam united the Middle East with Persia on the one hand and Egypt and North Africa on the other. There was a sort of Islamic colonisation of the East African coast, leading to the rise of prosperous port cities and kingdoms at Malindi, Mogadishu, Kilwa, and Zanzibar. As more and more people thronged Mecca for annual Haj, Jeddah, prospered as the entry point and the market of Haj started dominating the annual trading calendar of West Asia. At the other end of the Ocean, the first mosque in China–Memorial Mosque or Huaisheng Mosque was constructed in Canton/Guangzhou in 627 CE by Sa`d ibn Abi Waqqas, an uncle of Prophet. Modern historians doubt whether Waqqas had ever been to China but there is hardly any doubt about Muslim presence in China from the mid-seventh century. Probably Persian maritime traders had reached China directly long before, though the first account of the Siraf-Canton maritime route comes from the ninth-century Akhbar al Sin wa’l Hind (a description of India and China) of Suleiman.

Merchants from Red Sea ports or Persian Gulf coasts first stopped at Muscat or Suhar at Oman or Aden, and then either came to Cambay in Gujarat or went straight to Koulam Male in Malabar (Kerala). From there, mostly Indian Muslim (Gujarati Muslims, Mapillas from Kerala, Chuliyas from Tamil Nadu coast) merchants sailed up to South East Asian ports. Islam gave a tremendous boost to urbanisation all over Asia. In the Western flank, a long period of stability and domestic economic expansion, helped to create a large market. Similarly, in China, continuous movement of people from North to South, closer to coast, created another large market for consumption goods. A combination of this resulted in surging Asian commerce from the tenth century onward. Spice trade remained the chief attraction for foreign merchants but with large and stable empires, robust trade infrastructure, close contact with both South Asia and China and maritime Southeast Asia’s first standardised coinage, islands of Java and Bali were by now ready for the age of commerce. Indian merchants, especially from the coastal regions of Gujarat and South India were keen to participate in it.

Long before the rise of international commercial law, the bond of a common religion helped these merchant networks to conduct business across this vast geography, deal with the ever-present danger of natural disasters or man-made violence or extortion of local authorities (it also spawned a huge vocabulary of common maritime terms which were in circulation from Middle East to South East Asia for centuries like Nakhuda or the owner of the ship, Mu’alim or the pilot, Sahrang/Sareng or mate, Tandill or the officer in-charge of the seamen or Khallasi/Khalasi, Laskar or the crew – from Aden and Hormuz to Malacca–these terms became as familiar as the annual arrival and departure of foreign merchants). There were varieties of boats with exotic cargo but out in the water, they all were part of the same culture.

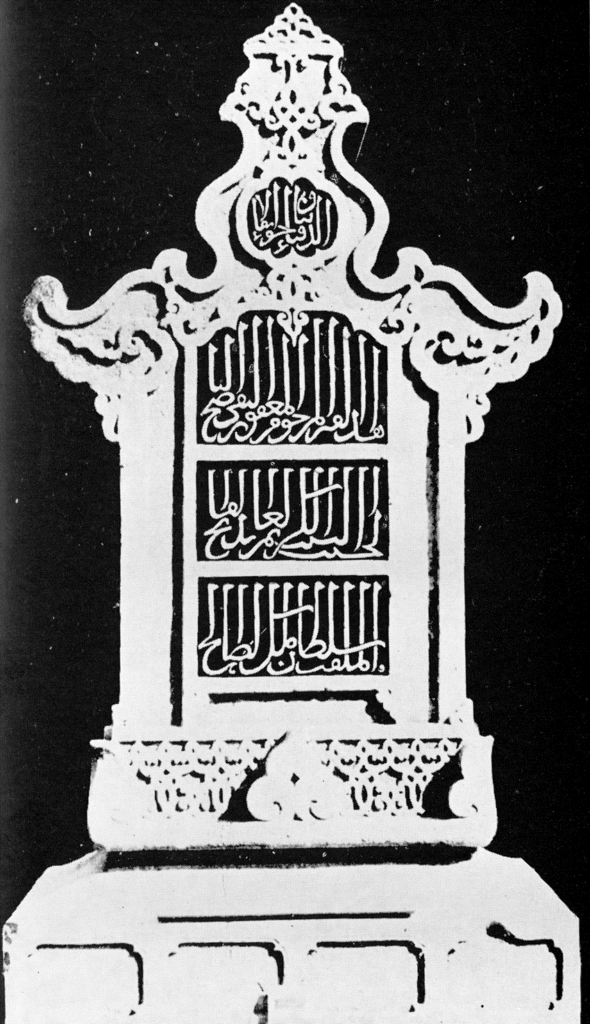

It was around the same time when the Islamic state of Samudra Pasai came about in early 14th century that the first series of Islamic tombs (barring an isolated case in the eleventh century) appeared in Java. These tomb stones closely resemble the style of similar tombs in contemporary Gujarat and in some cases, the tomb stones might have come from the Gujarati port of Cambay. Similarly in Java, Islam came through harbour kingdoms of Cirebon, Demok, Japara and Gresik, where foreign merchants frequented in large numbers. Traditional Javanese accounts attribute spread of Islam to the activities of a group of nine Saints, collectively known as Wali Sanga–though the exact list of the nine is not above dispute. The first of these saints (and his family dominates the list) was Malik Ibrahim, who came from Gujarat (though he was probably of Persian origin) and died at Gresik in 1419 CE.

Nuruddin ibn Ali ar-Raniri, a mystic from Rander, near Surat, lived for many years at the court of the Sultan of Aceh. His works are considered among the oldest Islamic scholarships in Southeast Asia. In a sweet celebration every March at Padang in Sumatra, small sachets of sugar are scattered from rooftops to celebrate the birthday of Sahul Hamid, an Indian preacher credited with introduction of Islam in Sumatra (festival of Serak Gulo). This is also a beautiful reminder of the Gujarati commercial association of this saint – Gujarat once exported sugar around the world (from the Sanskrit word khanda/khand, mainly used to denote pieces of jaggery, comes Persian qand, Arabic qandi, French candi and English candy).

Earlier it was believed that Islam was introduced mainly by Indian/Gujarati traders but now most historians believe that Islam came to Indonesia through multiple sources including Chinese, South Indian, and Gujarati. But there is no doubt that Islam reached Indonesia through maritime commercial sources and not riding on the back of a victorious army unlike Western or Central Asia. What the Indian Sufi mystics taught – a personal union with God – was not alien to what a Javanese Guru would earlier be teaching to his disciples. It was perhaps both Sufi and maritime influences that led to the blossoming of a moderate Islam in the archipelago and that too, without constituting a break with their rich, syncretistic social and cultural past, including Ramayana and other Hindu/Buddhist traditions.

Anindya Sengupta is a student of history and co-author of Laxminama: Monks, Merchants, Money and Mantra. He blogs at https://thetimeriver.blogspot.com/